economist

Nicolás Maduro tries to make thugocracy permanent in Venezuela

An unpopular regime’s attempt to impose dictatorship could end bloodily

IT COULD almost be a piece of contemporary art, rather than a tool of political struggle. Overlooked by a mango tree heavy with blushing fruit, a rope is strung across Avenida Sucre as it climbs through a comfortable middle-class area towards the forested slopes of Monte Ávila overlooking Caracas. Arranged beneath it are two distressed wooden beams, two pallets placed vertically, a wheel hub, a rusting metal housing for an electric transformer and several tree branches. They form a flimsy barricade watched over by a couple of dozen local residents.

Why are they blockading their own street? “Because we want this government to go,” explained María Antonieta Viso, the owner of a catering firm. They were taking part in a 24-hour “civic strike” on July 20th, called by the opposition coalition, Democratic Unity (MUD, from its initials in Spanish). Down the hill, across innumerable such roadblocks, the sting of tear gas signalled clashes between demonstrators and the National Guard, a militarised police force. The strike, repeated this week, was part of “Zero Hour”—a campaign of civil disobedience aimed at blocking a plan by Nicolás Maduro, Venezuela’s president, to install a constituent assembly with absolute powers.

Latest stories

-

“Isle of Dogs” lacks bite

-

Retail sales, producer prices, wages and exchange rates

-

Foreign reserves

-

What’s in Poland’s new memory law

-

Billy Graham’s gentle brand of evangelicalism

-

Infant deaths remain common in the developing world

Mr Maduro claims that the assembly is the “only way to achieve peace”, to provide Venezuelans with social welfare and to defend the country against what he claims is an “economic war” launched by America (though he provides no evidence of this). “What they are trying to do is to install the Cuban model in this country,” retorts Ms Viso. “We will all be screwed even if we take to the streets. There won’t be private property, my business will go to the state.” The long battle over power and policy in Venezuela that began when Hugo Chávez was elected president in 1998 has reached a critical point. Both government and opposition believe that they are fighting for survival against a backdrop of a failing economy, rising hunger and anarchy.

Chávez, a former army officer, proclaimed a “Bolivarian revolution”, named for Simón Bolívar, South America’s Venezuelan-born independence hero. He, too, summoned a constituent assembly, which drew up a new constitution and which he used to take control of the judiciary and the electoral authority. For much of his 14 years in power he had the support of most Venezuelans, thanks partly to his charismatic claim to represent a downtrodden majority and to the flaws of an opposition identified with an uncaring elite. But above all the soaring price of oil gave him an unprecedented windfall, some of which he showered on social programmes in the long-neglected ranchos (shantytowns). A consumption boom, magnified by an overvalued currency, kept the middle class quiescent. He governed at first through a broad coalition of army officers, far-left politicians and intellectuals.

Angered by opposition attempts to unseat him and influenced by Fidel Castro, Chávez pushed Venezuela towards state socialism after 2007. Economic distortions accumulated, along with corruption and debt. Before he died of cancer in 2013, Chávez chose Mr Maduro, a former bus driver and pro-Cuban activist, as his successor.

From Chávez to Maduro

Mr Maduro, however, lacks Chávez’s political skills and popular support. And he has had to grapple with the plunge in the oil price. Years of controls and the takeover of more than 1,500 private businesses and many farms mean that Venezuela now produces little except oil, and imports almost everything else. The government is desperate to avoid defaulting on its debt, since that would lead to creditors seizing oil shipments and assets abroad.

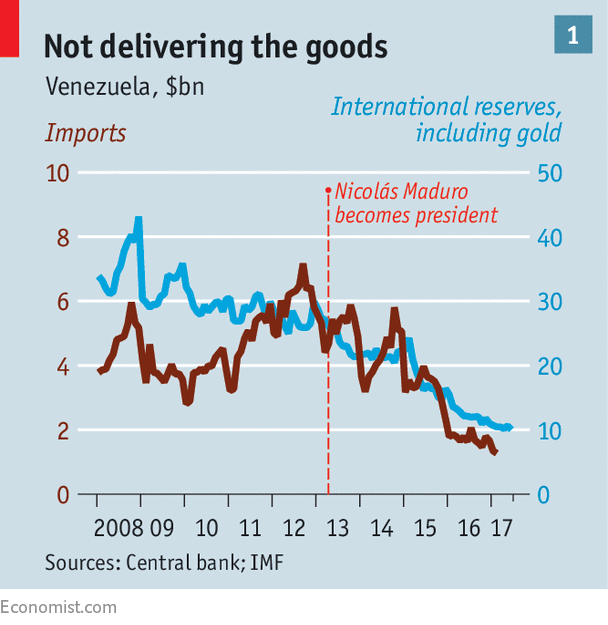

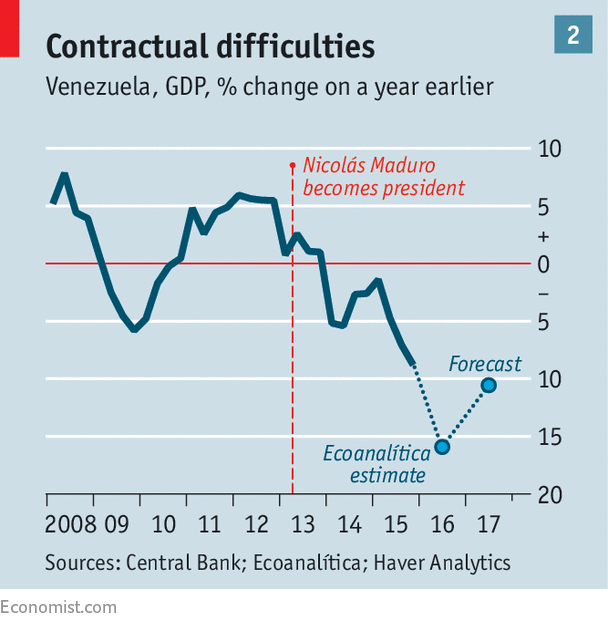

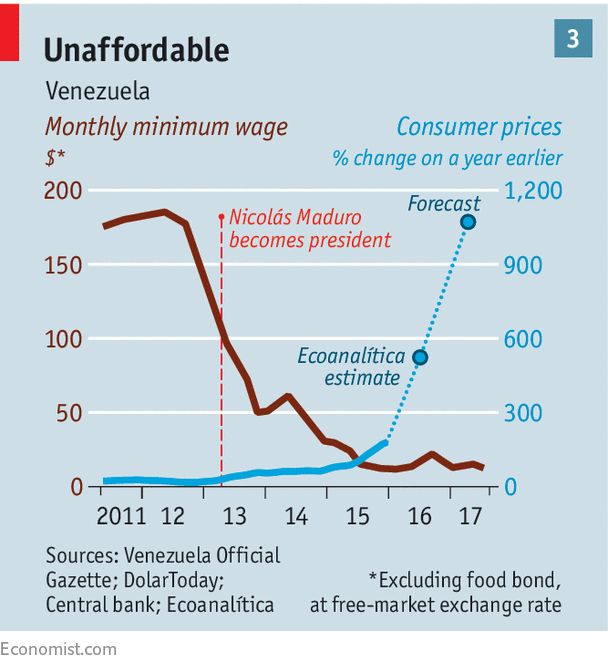

Rather than reform the economy, Mr Maduro has simply squeezed it, applying a tourniquet to imports (see chart 1). The government has no clear strategy for external financing, and the fiscal deficit, mainly financed by printing money, is out of control, says Efraín Velázquez, the president of the National Economic Council, a quasi-official body. The result: “you can’t have growth and will have a lot of inflation.” Between 2013 and the end of this year, GDP will have contracted by more than 35% (see chart 2). What this means for most Venezuelans is penury.

Near Plaza Pérez Bonalde, a leafy enclave in the gritty district of Catia in western Caracas, 100 or so people, mainly women, queue up outside a bakery. They hope to get a ration of eight bread rolls for the subsidised price of 1,200 bolívares (less than $0.15 at the black-market exchange rate). “At least it’s something, because everything else is so expensive now,” says Sol Ciré, a mother of two. She is unemployed, having lost her job at a defunct government hypermarket. Her fate stems from a change of government strategy.

Generalised price controls had generated widespread shortages and embarrassingly long queues. Instead, the government has put the army in charge of a subsidised food-distribution system, known as CLAP and modelled on Cuba’s ration book. Up to 30% of families get this dole of staple products regularly, reckons Asdrúbal Oliveros of Ecoanalítica, an economic consultancy. They are chosen not according to need but according to their political importance to the government.

On the breadline

At the same time, the government has relaxed price controls (bread is an exception). In Catia’s main market, which spills into the surrounding streets, food is abundant, but pricey. A chicken costs 7,600 bolívares and bananas 1,200 a kilo. Most people don’t have dollars to change on the black market: they must live on the minimum wage of 250,000 bolívares. The result is that four out of five households were poor last year, their income insufficient to cover basic needs, according to a survey by three universities. Medicines remain scarce. Walk down many streets in Caracas and you may be approached by a beggar.

All this has taken a heavy toll on the government’s support. Mr Maduro won only 50.6% of the vote in a presidential election in 2013, a result questioned by his opponent, Henrique Capriles. In a parliamentary election in December 2015 the opposition won a two-thirds majority—enough to censure ministers and change the constitution.

In the government’s eyes, the opposition is bent on overthrowing an elected president—the aim of protests in 2014, after which Leopoldo López, an opposition leader, was jailed on trumped-up charges. In response, it has resorted to legal chicanery. If Chávez often violated the letter of his own constitution, Mr Maduro tore it up.

Before the new parliament took over, the government used the old one to preserve its control of the supreme court by replacing justices due to retire. The court then unseated three legislators, eliminating the opposition’s two-thirds majority. Mr Maduro has ruled by decree. The tame electoral tribunal quashed an opposition attempt to trigger a referendum to recall the president—a device Chávez put in the constitution. It postponed regional elections due to take place last December.

In March the court issued decrees stripping the parliament of all powers. That seemed to be because foreign investors take more seriously than the government a constitutional provision under which only the parliament can approve foreign loans. Although partially withdrawn, the decrees were the trigger for a confrontation that continues. They opened up fractures in chavismo—notably the public opposition of Luisa Ortega, the attorney-general since 2007 (who had jailed Mr López). Mr Maduro’s announcement on May 1st that he would convene the constituent assembly intensified both trends.

Chávez’s constitution was drawn up by a democratically elected constituent assembly, convoked by referendum. Mr Maduro is following a script from Mussolini. He has called the assembly by decree. It will have a “citizen, worker, communal and peasant-farmer” character, he said. What this means is that 181 members will be chosen by government-controlled “sectoral” groups such as students, fishermen and unions. Another 364 members will be directly elected, but in gerrymandered fashion: each of Venezuela’s 340 municipalities will choose one. Small towns are under the government’s thumb; cities, where the opposition is a majority, will get only one extra representative.

Datanálisis, a reliable pollster, finds that two-thirds of respondents reject the constituent assembly, more than 80% think it unnecessary to change the constitution and only 23% approve of Mr Maduro. At just two weeks’ notice, on July 16th almost 7.5m Venezuelans turned out for an unofficial plebiscite organised by the opposition. Almost all of them voted to reject the assembly, to call on the army to defend the constitution and for a presidential election by next year (when one is due).

Few doubt that the assembly will be a puppet-body and the vote on July 30th, which the opposition will boycott, will be inflated. The government counts on the 4.5m people who are employed in the public sector or in communal bodies. Those who fail to turn out risk losing not just their job but their CLAP food rations. Additional pressure to vote in chavista neighbourhoods comes from the colectivos—regime-sponsored armed thugs on motorbikes. Officials have said the assembly will not only write a new constitution but will assume supreme power, sacking Ms Ortega and replacing the parliament, whose building it will occupy. It will give Mr Maduro a slightly larger figleaf than the supreme court for a dictatorship of the minority.

Yet the president will find it hard to make this stick. “How do you govern the country with 75% against you?” asks Mr Capriles. “I think he’s trapped.” For the past four months the opposition has held almost daily protests. These have a ritual quality. To prevent demonstrators reaching the city centre, or blocking the main motorway through Caracas, the National Guard fires volleys of tear gas, buckshot—and occasionally bullets. Younger radicals, known as the “Resistance”, press forward, throwing stones from behind makeshift shields. Similar scenes take place across the country. Looting is commonplace. In these clashes, over 100 people have died. More than 400 protesters are now prisoners, including several opposition politicians. After the parliament named 33 justices to a rival supreme court on July 21st, the government arrested three of them.

Resistance isn’t futile

Mr Maduro has more worries. The first is his own side. Chavistastrongholds are wavering. In the bread queue in Catia, several people say they are against the assembly. The opposition managed to set up voting stations for its plebiscite there: at one, a woman died when a colectivo fired on voters. “Some people have left us and gone over to the other side,” admits a local official. “But it’s very difficult for a chavista to support the opposition,” she adds. Chávez is still viewed favourably by 53% of Venezuelans, according to Datanálisis.

Rather, a new movement of “critical” or “democratic” chavistas, including Ms Ortega, several former ministers and recently retired generals, has publicly called for the scrapping of the assembly and the upholding of the constitution. When they held a press conference at a modest hotel on July 21st, some 300 regime supporters outside tried to drown them out with loud music and chants of “traitors”.

Then there is the army. The regime has co-opted it, turning it into a faction-ridden, politicised and top-heavy moneymaking operation, with more than 2,000 generals (where 200 used to suffice). Mr Maduro has given them control over food imports and distribution, ports and airports, a bank and the mining industry. Many generals have grown rich by buying dollars at the lowest official exchange rate of $1=10 bolívares, intended for food imports, and selling them at the black market rate of 9,000. Others smuggle petrol or drugs.

Murmuring in the ranks

An “undercurrent of muttering” among junior officers is checked by a network of political commissars and snoops installed by Chávez, says José Machillanda, of Simón Bolívar University in Caracas. At the top, several thousand Cuban security personnel guard Mr Maduro and the 30-40 leaders who form the regime’s core.

But the assembly has tested the army’s loyalty to Mr Maduro. He twice reshuffled senior ranks in the past two months. Caracas is alive with rumours of an impending pronunciamento, in which the army withdraws its support for the regime.

Another acute threat to Mr Maduro is the economy. The rot has spread to the oil industry, Venezuela’s mainstay. According to OPEC, since 2015 the country’s oil output has fallen by 400,000 barrels per day (or around 17%). This is the long-term price of Chávez’s decision to turn PDVSA, the once efficient state oil company, into an arm of the welfare state.

Foreign-exchange reserves hover around $10bn, according to the Central Bank. Economists expect the government to make $3.5bn in debt payments due in the autumn, but it will struggle to find the $8.5bn it needs to avoid default next year. China, a big paymaster, is reluctant to lend more. Russia may be Mr Maduro’s best hope, but it worries about getting entangled in possible American sanctions against Venezuela.

The fourth problem Mr Maduro faces is that the region has become less friendly to him. Chávez enjoyed the solidarity of other left-wing governments in Latin America. Many are no longer there, or have distanced themselves. Venezuela has been suspended from Mercosur, a trade group; it could be expelled if the assembly goes ahead, says Argentina’s foreign minister. The regime showed that it cares about its standing in the region by the big diplomatic effort it made in June to prevent its suspension from the Organisation of American States.

Many in Caracas assumed that Mr Maduro intended the assembly as a bargaining chip, to be withdrawn in return for concessions by the opposition. If so, he may be trapped by the forces of radicalisation he has unleashed. Diosdado Cabello, a retired army officer who is his chief rival within the regime, appears to see the assembly as his route to power. Back down now, and Mr Maduro risks losing face among his hard-core supporters.

Venezuela thus stands at a junction. One road involves a negotiation that might either fix a calendar for a free and fair election, or that might see Mr Maduro and other regime leaders depart. The opposition is mistrustful after talks brokered by the Vatican and José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, a former Spanish prime minister, broke down last year when it quickly became clear that the government was not prepared to restore constitutional rule. Mr Zapatero was a conduit for a move that saw Mr López transferred from prison to house arrest this month. He is in Caracas again this week.

The city hums with rumours of a new mediation effort led by a shifting kaleidoscope of foreign governments. But conditions do not yet seem ripe. “The government sees the cost of leaving power as very high, that they would be destroyed and persecuted,” reckons Luis Vicente León of Datanálisis. The opposition is suspicious, too. “To return to political negotiations we have to have real signs that the government is prepared to change,” observes Freddy Guevara, the deputy leader of Mr López’s party.

That probably requires a military pronunciamento. But the army “looks at the opposition and doesn’t see any guarantees that they would be able to run the country”, says a foreign diplomat. The MUD has worked well as an electoral coalition, and its plebiscite was impressive. It has published a programme for a government of national unity. But, crucially, it lacks an agreed leader with a mandate to negotiate. “The opposition is stuck together with chewing gum,” says Mr León.

Anomie and anarchy

Barring a negotiation, the other route looks bleak. There is a growing sense of anomie and anarchy. On the opposition side, there is desperation in the self-barricading of its own neighbourhoods, an action which does little to hurt the government. Social media have been vital in undermining the regime’s control of information. But they also spread rumours and undermine moderation. Middle-class caraqueños are reading books on non-violent resistance. But on the streets many protesters express mistrust for the MUD. The “Resistance” is well-organised and trained. It would not be hard for it to take up arms.

For its part, the chavista block is splintering. The National Guard now raids properties in chavista areas at night, because they are being fired on by disgruntled residents. “There’s a growing attitude of ‘don’t mess with me’,” says Mr Machillanda.

Mr Maduro and his core of civilian leftists admire Cuba but they do not command a disciplined revolutionary state, capable of imposing its will across Venezuela’s vast territory. The 100 or so dead in the protests are fewer than are killed each weekend in lawless poor neighbourhoods. The “Bolivarian revolution” has created a state run by rival mafias and undermined from within by corruption.

“They could try to Cubanise the country,” says Mr Capriles. “But whether Venezuelans accept that is another matter.” Given the intensity of Venezuela’s confrontation, it has suffered remarkably little political violence. Sadly, that may now change. If Mr Maduro shuts down all hope of political change, it may take many more deaths to break the deadlock.